It’s easy to outcompete people who are smarter than you as long as you understand how to develop T-shaped skills.

If you do this, you can outperform those who are much, much more intelligent than you.

In this post, I’ll explain how to gain T-shaped knowledge. And how to build a “lattice work of mental models” (instead of excelling in only one specific area).

With this multi-disciplinary way of thinking, you’ll run laps around your competitors.

Why T-shaped skills give you an edge

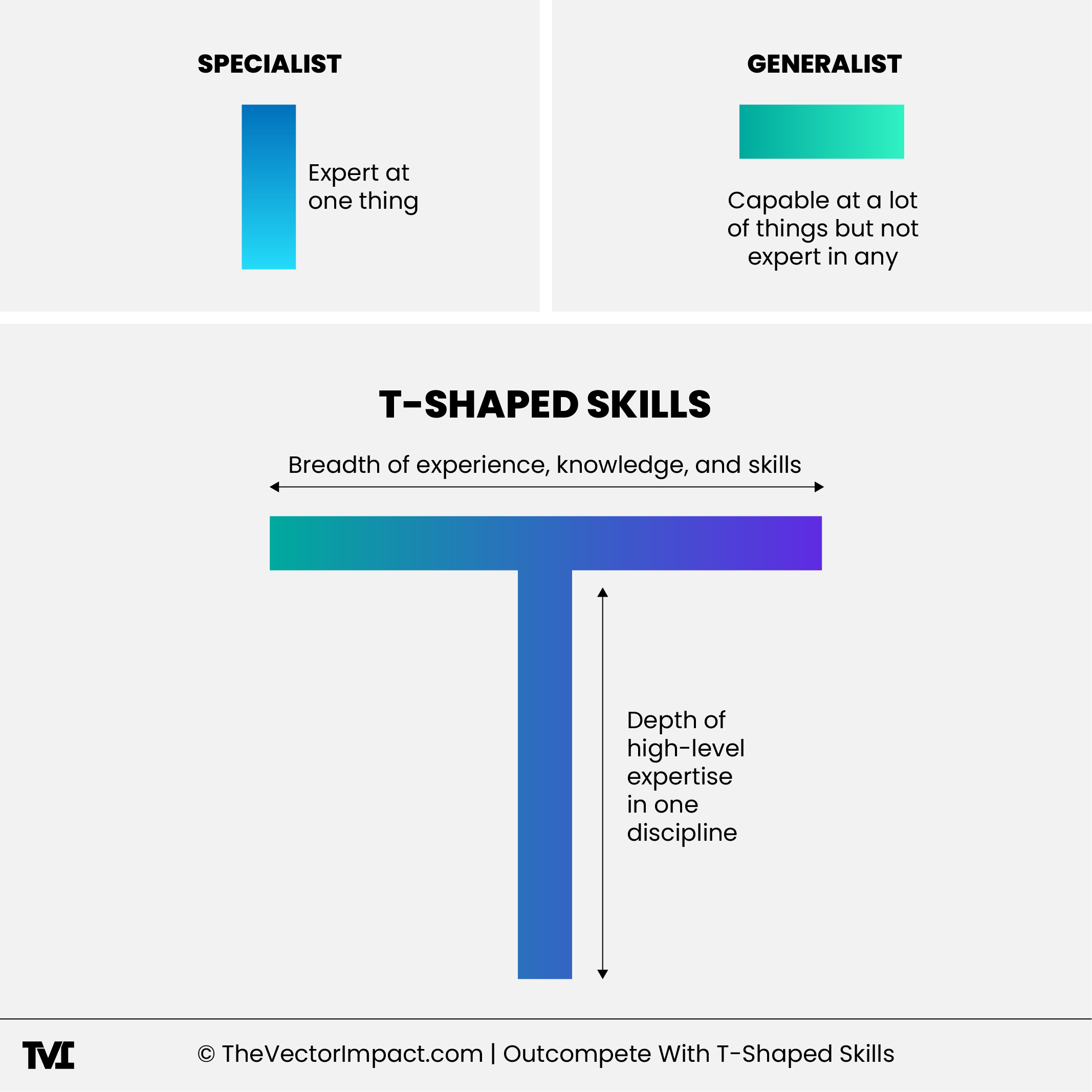

T-shaped skills are like a superpower combo: deep expertise in one area (that’s the vertical part of the “T”), plus broad knowledge across other fields (the horizontal part). Think of it as being both a specialist and a well-rounded human.

Why does this matter?

Because while someone else might be a genius in one hyper-specific thing, the T-shaped person can connect dots across different domains, ask better questions, and adapt faster.

In the professional world, the person who can translate between teams, spot patterns others miss, and jump into new challenges without flailing—that’s the person who wins.

To read more on building key skills, check out these posts:

The number one problem with smart people

Pay attention—this will be your entry point to competing with them.

A lot of intelligent people suffer from something called “domain dependence.”

Domain dependence means that all of their knowledge was built in a single silo. They’ve only developed credibility, experience, know-how, and insight through that one specific area of knowledge or domain.

On the one hand, you do want to have a deep well of knowledge when it comes to a specific topic because it’s how you stand out as an expert. It’s how you get quality insights.

But there’s a dangerous downside to it.

Charlie Munger was talking about this when he said: “To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

If you’re only thinking in one certain way because you’re only good in one specific domain, you can only look at the problems and challenges inside of that industry through one lens.

This is why it’s common to see exceptionally accomplished people, some who even go on to win Nobel prizes in specific scientific fields, when it’s not their original discipline. They can look at it from an outsider’s perspective, and they can see things that someone who has domain dependence cannot see.

Since they are not suffering from “man with a hammer syndrome,” they understand that not everything is a nail. They’re aware that screws can be turned that are outside of what’s typical. They can make connections others can’t.

Why you need deep expertise and broad knowledge

One of my favorite examples of outsider thinking comes from Daniel Kanheman, author of the book “Thinking Fast and Slow,” and his research partner, Amos Tversky:

Economics had long been dominated by theories assuming humans make rational choices to maximize their utility.

But these psychologists observed actual human behavior and found consistent patterns of irrationality. They understood that real people use mental shortcuts (heuristics) that lead to predictable errors (biases).

Their concept of “loss aversion” explains why investors hold onto losing stocks too long, why homeowners refuse fair offers in declining markets, and why negotiations fail when framed differently by each party.

Traditional economists could not see these patterns because they were too entrenched in models that assumed rational behavior.

It took outsiders to create behavioral economics, now a cornerstone of the field.

👆🏾This is how you can outcompete people who are a lot smarter than you and become that T-shaped phenomenon.

Reading people like Kahneman was a gateway for me to learn about concepts like heuristics. This led to understanding heuristics, which led me to understanding the ones others were using and incorporating them to get ahead.

These concepts all became part of my latticework of mental models, which is the perfect segue to the next section…

T-shaped skills start with mental models

When Charlie Munger talked about building a “latticework of mental models,” he meant this:

The smartest thinkers don’t rely on only one way of seeing the world.

They collect a variety of tools for thinking that help them solve problems, make decisions, and spot opportunities across different situations.

At the most basic level, for better or worse, we all have mental models we fall back on daily (whether we realize it or not):

@farnamstreet Mental models, explained from someone who literally wrote the book on them. #mentalmodels #farnamstreet #thinking #decisions ♬ original sound – Farnam Street

One example is opportunity cost—the idea that every choice has a tradeoff. If you spend your Saturday bingeing Netflix, that time isn’t available for studying, investing in meaningful relationships, or working toward personal goals.

Just understanding this concept can help you make better decisions, faster.

The more mental models you collect (from psychology, economics, science, design, etc.), the more versatile and creative your thinking becomes.

Mental models are not the same thing as T-shaped skills—but they support building them.

When you have multi-disciplinary thinking, the combined power of your knowledge allows you to be a versatile, nimble, creative thinker against your competition—who, if they’re stuck in domain dependence, often has stale, entrenched ideas.

How do you put this into practice? Gain that expertise in one specific area, yes. AND gain knowledge and build complementary skills—picking up mental models along the way to help you become T-shaped.

Multi-disciplinary thinking in action

For example, understanding biology is great if you want to understand how to buy and sell stocks.

You see, when it comes to the stock market, emotions drive many decisions because we have an animalistic biological nature, thanks to evolution.

So if you have a good grasp of biology, you may do better at buying and selling stocks than the average person. Because you understand human nature—and that people tend to buy high and sell low, as their biology dictates.

Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, shows this approach in action, too. Though he focused on quantum physics, he often explored biology, computing, and even safe-cracking.

When the Challenger space shuttle disaster occurred, it wasn’t the aerospace specialists but Feynman who demonstrated the O-ring failure by simply placing a rubber ring in ice water during the investigation.

His outsider view, combined with fundamental physics knowledge, solved what specialist engineers had missed.

To get ahead, T-shaped people find the intersections where different disciplines and insights meet.

Digging into heuristics and mental models

There are countless disciplines to study and mental models to use.

For fields of study, you could look at places like biology or evolutionary psychology.

For heuristics, you can think of concepts like loss aversion and incentives.

For me, incentives is the number one most useful heuristic I have ever used.

Like Munger said, if you know the incentive, you know the outcome. It’s as close as you can come to predicting human behavior.

It’s also a concept a lot of smart people struggle to understand, but it comes down to this:

People do what they’re incentivized to do—period.

Incentives are the hidden forces driving decisions, whether it’s chasing a raise, ghosting a group project, or posting on TikTok for the dopamine. In other words, the incentive could be attention, status, convenience, or avoiding pain.

If you want to understand someone’s behavior (including your own), follow the rewards.

Something else people struggle with is how to use second-order thinking.

This means thinking beyond the immediate result of a decision. Instead of only asking “What will happen first?,” you should ask, “And then what will happen after that? And after that?”

People who understand these concepts (human behavior and longer-term consequences) often make better decisions than those who only scratch the surface level of a plan.

Take, for example, something like the minimum wage.

Some people would say that raising the minimum wage by a large amount is good because people will get paid more, but as a result of that, companies may raise prices or decide not to hire workers at that rate at all.

Heuristics and mental models give you the tools to cut through complexity, apply insight across different fields, and see the second- and third-order effects others miss.

When you stack models like incentives, loss aversion, or second-order thinking on top of your core expertise, you become more adaptable, more strategic, and way harder to outthink.

That’s the real edge of a T-shaped skillset: not just knowing more, but thinking better.

What T-shaped skills look like in the wild

I’m reminded of a perfect example from my own business. I help skilled professionals market their products and services, so they can sign more clients.

Many of my clients are only good at the one thing they’re known for (hello, domain dependence), but they don’t know the complementary skills that would help them market their work.

I have a client who is a therapist. She’s 62 years old. She’s a Harvard-trained psychotherapist, PhD. She also trained under the Dalai Lama, lived in Tibet for 6 years, and mentored directly underneath them, which means she has a background as a mindfulness practitioner as well.

When she came to me, she was skilled at helping people overcome their anxiety with the combination of psychotherapy and mindfulness. But my team had to help her build T-shaped skills so she could make money.

One part of the T was teaching her the skill of content creation. She didn’t become the best content creator in the world, but she was good enough to get attention so that clients would become aware of her.

We taught her how to run sales calls, which is a skill that helped her close 17 clients and led to her making $40,000 in a single month. We taught her skills like lead generation, how to talk to people, and how to have conversations that led to booking sales calls and making money.

You can see how, in this field I’m working in, there are a lot of people who are very skilled at what they do, but they are only good at that part.

They need support surrounding the crucial set of skills that lead to making money. This is why I teach them to become T-shaped and why you want to build those T-shaped skills, too.

Want another example? Take Steve Jobs. He didn’t even know how to code himself.

Think about that for a second.

His main skill wasn’t computing or engineering—it was design and user experience (UX).

He made Apple stand out by connecting computing with calligraphy, music, consumer psychology, and simple design. Jobs often mentioned a calligraphy class he “dropped in on” that shaped Apple’s typography and design aesthetic. This seemingly unrelated knowledge became a huge competitive advantage in the computing industry.

For me, the skill of writing built my foundation. It became a gateway to developing many complementary skills that helped me build the business I have today. Skills like marketing, sales, video content creation, negotiating, operational skills, financial tracking, and more.

I’ve learned social skills so that I can build a network of fellow entrepreneurs, collaborators, partners, peers, operators, freelancers, agency owners—this apparatus of human beings that I leverage and work with to grow my business.

You want to know a little bit about a lot.

Apply this to your life (and smoke the competition)

One of the most valuable things you can do is bring an outsider’s perspective into your core discipline.

That’s specifically what I did with my career.

I was a personal development writer, and a lot of people in my niche primarily talked about basic self-help tenets.

But I started reading about disciplines outside of self-help—things like psychology, evolutionary psychology, statistics, and probabilities—things of that nature.

I read people like Charlie Munger and Nassim Taleb, whose ideas were relevant to what I was talking about. This gave me the chance to be unique.

Let’s take Nassim Taleb as an example. He teaches this idea of convexity, which means that if you want to live a successful life, you should find opportunities that have a known downside (that you can handle) and a high and infinite upside.

So I applied that when teaching people how to improve their situations, and I also used it in my own life.

For example, when I produce a product like a book, I know the known downside of the minimum amount of books I can sell—which is zero— and the amount of money that I invested in creating the books. But I know that there’s high leverage.

So, I started talking about these concepts that were outside of my niche, and put them inside of my niche. I wove them into my work with basic self-improvement tenets. And then my own lattice work of mental models that I developed through trial and error and experimentation. I injected all of it into my writing and into my business in a way that made it easier to compete with people who are smarter than me.

Since I’ve developed the ability to articulate ideas in an entertaining way through the lens of blogging, which is a skill that I picked up. I package information properly, like writing headlines, which is a skill that I learned from the art of copywriting. I combine both of these with my ability to discuss outside perspectives. All of these skills together led to me to make more money and attract more attention than other experts and writers in my niche.

The best part of this approach is how it grows over time. Each new mental model or idea from another field doesn’t just add to what you know—it multiplies it, creating many more possible connections and insights. By intentionally developing your T-shaped skills and building your lattice work of mental models, you position yourself to not just compete with, but consistently outperform, individuals of higher raw intelligence who remain trapped in domain dependence. Today’s world rewards connectors more than specialists, and the winners are the ones who link different fields and share insights across them. By becoming T-shaped, you’ll spot opportunities and solutions others simply can’t see.